You buy a new computer. You turn it on. A screen pops up:

Installing Windows 98

You may have told the computer vendor that you didn’t want Windows 98: that’s just tough. Microsoft essentially taxes every computer purchased at mainstream outlets by forcing the vendors to buy a copy of Windows for every computer they sell regardless of whether or not the purchaser wants it.

Anyway, suppose you are going to install Linux instead. Suppose that when the copyright notice pops up asking you to click “OK” to agree to the terms, you just click “NO”. Will you get your money back, like they promise? Not if you buy your computer from Dell.

More importantly, if you do click “OK”, have you made a contract with Microsoft in which you agree to their copyright terms?

Maybe. Maybe not.

You see, it is well established in law (under Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code, which governs interstate commerce in the U.S.) that whenever you buy a product from any vendor, there is an implied contract, a “warrant of merchantability” that states that the product is fit for ordinary use. Now, I don’t think anybody in their right mind would say that Windows 98 is fit for “ordinary use”. One of the most profound miracles of modern consumerism is the way everyone just accepts that Windows is the best we can do, because, after all, it comes with the computer, and the computer people must know about these things… Just today, for example, on my computer, it messed up the graphics in a computer game, and disabled all the hotlinks in my web browser. This is only about the 744th problem I’ve had with Windows. This month.

So, can you get your money back? No. Because Microsoft, in their software agreement, disclaims all “implied warrants of merchantability”. Well, wait a minute… maybe you can. You see, such disclaimers are not valid unless they are agreed to before purchase, by the vendor and the customer. So maybe you can. But you won’t. Microsoft will simply refuse to give you your money back.

Now I imagine that if you got your lawyer after them and made a lot of noise about it, you probably would get your money back. But how is that possible? Don’t these big corporations know what the law is? And how can Microsoft get away with making it a condition of purchase of Microsoft Agent that none of the little animations may be used to “disparage” Microsoft Corporation?

* * *

If you listen long enough to people like Jack Valenti (the Motion Picture Association of America) you might get the impression that Copyright has existed forever, and, indeed, was passed down to us by God himself on Mount Sinai. Jack Valenti is the guy who had incredible fits about the fact that the Canadian government tried to encourage a home-grown film industry when Hollywood was quite capable of providing culturally enriching products like “Earnest Saves Christmas” without any help from Canadians, thank you.

Something like copyright was first invented in 1557 by the Guild of Printers in London, England, and made into law by Queen Mary. What she did was give complete control over all printed text to The Stationer’s Company. It was more in the nature of a monopoly than legal protection. These printers even had exclusive rights to print the works of dead authors like Plato and Aristotle and Gore Vidal. In exchange for this monopoly– get this– the printers were to assist the Crown in preventing the distribution of seditious and heretical works. That includes works that question the application of copyright law. Sounds like the FCC’s philosophy of television licensing.

They were addressing a real problem. According to Adrian Johns, of the University of California, there were 80 pirated copies of Martin Luther’s work for every legitimate one.

In 1710, after the pleadings of noted writers like John Locke and Daniel Defoe, Queen Anne revised the law to give more rights to the authors. The monopolies didn’t give up without a fight: they took their case to court. They won a few concessions. The important thing is that such a thing as “copyright” now existed.

Here is where a very interesting debate took place, and a signal ruling was made by the British courts. The monopolies argued that intellectual property belongs absolutely to whoever “owns” it. They argued that intellectual property is essentially similar to physical property. If I own a table or a chair, I can keep it, or I can sell it to someone else, or I can burn it so no one else can ever use it. And the same goes with my words and ideas. If I choose to, I can stop anyone else from ever using them. On the other side, Samuel Johnson argued that society rightly benefits from the free distribution of ideas, therefore, it is in the public interest to limit the scope of copyright. The products of the human mind belong to humanity. Samuel Johnson didn’t argue, but should have, that ideas are by nature a communal activity, and therefore, cannot be imprisoned by one individual under the name of “copyright”.

In 1774, the House of Lords agreed with Johnson and declared that, for the general good of society, intellectual property belongs to the general public. However, to promote the creation and improvement of these works, some temporary rights over distribution of these works can be granted to the author.

The Founding Fathers of America didn’t like copyright as a matter of principle, because, again, they believed that ideas belong to everyone, but agreed that a short-term monopoly over distribution served the greater public interest of increasing the store of knowledge, so they also agreed, in 1790, to a 14-year copyright period with the option to renew for one more 14-year period.

Those wild and crazy revolutionaries in France had the cool idea– 200 years before Wired Magazine– of abolishing copyright altogether. But this had the peculiar effect of reducing the number of published works. Since a publisher couldn’t prevent others from copying his works, he couldn’t make money, so he simply wouldn’t publish. So many important works fell out of print. Eventually, Robespierre and his gang restored the old copyright law– probably just as they were about to pen their own memoirs. It’s too bad they gave up so soon. It would have been interesting to see who things would have worked out over a period of fifty or one hundred years. Chaos theory, you know.

Well, publishers and authors didn’t just sit back and accept the current state of affairs. Over the years since 1790, they have been wheedling away at Congress seeking greater and greater copyright protection, and they’ve succeeded to a large extent. Copyright now extends to the life of the author plus 50 years, and has been extended to everything from music to computer chip diagrams. The descendants of the great writers of the early 20th century are especially keen on extending this period: they get to collect royalties from Grandpa’s work as long as the copyright is in effect. The copyright on “Gone With the Wind”, for example, would have and should have expired in 1993. Congress has generously extended it to 2032. Generously to somebody (the author, Margaret Mitchell, is long dead.). And don’t assume they’ll stop there– the trend is clear. By the time 2032 rolls around, they’ll have extended it again, because they are not listening to consumers or the average citizen or those really smart people who insisted all copyrights should be temporary. They’re out on some yacht owned by Houghton Mifflin.

Richard Stallman at MIT founded the first anti-copyright organization, since the Reign of Terror, in 1984, the Free Software Foundation. John Perry Barlow founded the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which is an advocacy group for electronic civil liberties. Barlow used to write for the Grateful Dead. The Grateful Dead defied the more anal-retentive music establishment by encouraging their fans to record their concerts and copy their tapes for personal use. The interesting result was that they increased their audience, sold more concert tickets and albums, and did quite well, thank you.

Facts cannot be copyrighted. DNA, according to the U.S. patent office, can be copyrighted. Data bases could not be copyrighted until recently, because they were believed to be collections of facts. So if you published a list of phone numbers of people on your block, anybody could copy it. What an outrage! Then everyone would know who lived on your block! Well, Congress is in the process of fixing that one up: they will allow publishers to copyright their “collections” of facts.

What does this mean exactly? The publishers argue that it means that instead of just copying someone else’s list of your neighbors and their phone numbers, you will have to go door-to-door yourself and collect the information over again. Why do I have a feeling that pretty soon, that won’t be legal either. The copyright police will be out there beating up Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Some companies in the U.S. have won the right to publish court verdicts exclusively. So, in essence, they are copyrighting the law. This could have some advantages. The next time someone charges you with infringing on their copyright, tell them that that law is copyrighted and they can’t use it. If that fails, tell them that you have copyrighted the story of how you stole their copyrights and they can’t use this information without your permission.

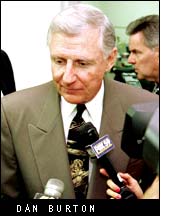

The trouble is that Congress chooses to accept loads of input from owners of various copyrights, like Disney and Time Warner, but almost no input from consumers or consumer groups. Or, more accurately perhaps, they ignore the input from consumers. Consumers, you see, don’t put out the big bucks for election campaigns. The new laws being passed all favour copyright owners.

What really irritates me is way these “improvements” are presented as if they will help the poor, struggling “artists” to be paid fairly. That’s the pr campaign. This is completely untrue. These new laws will help big corporations, who have been ripping artists off for years, rip off the consumer as well. The artist, you see, only gets about $1.00 or so per CD, if they are really lucky and established and they had a good lawyer when they signed their first contract. The record company gets a much bigger chunk, so they will gain the most. Some of the most successful recording artists are, in fact, up to their ears in hock to their record companies. How can that be? They are selling millions of recordings? Well, it’s those clever little contracts. You’re a young artist. Your fondest dream is to be a “recording star”. A record company says, “we’ll make your dream come true. All you have to do is… sign… here.”

In Canada, they are about to impose a .50 per cassette “tax” on blank tapes in order to compensate copyright owners for the money they are supposedly losing through home taping. This stinks for several reasons.

-

nobody has proven that they have lost a penny through home taping. If the experience of the Grateful Dead is any indication, they have, in fact, made more money through home taping, through the “free advertising and trial product” effect. Check out your own collection: don’t you own a lot of CD’s by artists you first heard on tape? Now, maybe people who listen to Celine Dion and Walter Ostanek are not as honest as people who listen to the Grateful Dead. That’s their problem.

-

a lot of these tapes are used to make copies of CD’s so the user can play the music in the car, or make “compilation” tapes, of selections from various CD’s. This is perfectly within the rights of the consumer under established copyright law. And remember– it is the publishing industry that wants to insist that copyright applies to the intellectual material, not the physical disk (so they could argue against piracy in the first place). If that is true, than anyone certainly has the right to make as many copies as he or she wants to for personal use.

-

what if I happen to like taping my own original songs? Not only do I have to pay extra for my blank tapes even though I’m not stealing anybody’s music, but I don’t get a share of the booty. You might argue that I don’t have any recordings out there that people won’t buy because they can tape my music off the radio instead. But the truth is, they don’t know if anybody would have bought a Celine Dion record either. They really don’t.

So what we have is a bunch of big powerful businessmen making a money grab, and the government goes along with it because the average consumer doesn’t have a high-priced lobbyist in Ottawa to argue our case.

[more later…]

For a terrific discussion of software licensing, click HERE.