Robert Leroy Parker, alias Butch Cassidy, was born in Beaver, Utah, on April 13, 1866. He was the first of 13 children. His mother and father were Mormons, trying to eke out a living on a small homestead that was eventually taken away from them by the Mormon Church. At 16, Butch met a drifter and cattle rustler named Mike Cassidy. Cassidy taught Butch how to shoot, and, possibly, why he would want to know how to shoot. At 18, Butch left home and began his long career as an itinerant outlaw. Eventually, he adopted Cassidy’s last name. He was called “Butch” after one of his infrequent attempts to earn an honest living, as a butcher.

Harry Longabaugh, alias The Sundance Kid, was born in Pennsylvania in the Spring of 1867. At the age of 15, he left home and traveled to Durango with a cousin. He drifted around taking jobs here and there, until the harsh winter of 1884, when disastrous winter storms in the west wiped out most large herds of cattle, and the jobs tending them. In 1886, he stole his first horse. He was caught. He escaped. He was caught again, and escaped again. A newspaper published a headline story about his adventures. He wrote a fairly literate letter to the editor, disputing some of the points, but disarmingly conceding that he was, indeed, a thief.

It was around this time that the Sundance Kid met a woman named Etta and took her with him to the famous outlaw refuge, the Hole-in-the-Wall, in Wyoming. Who was she? Where did she come from? Why was she traveling around the wild west in the company of a known outlaw? She registered in hotels as Etta “Place”, but Place was Sundance’s mother’s last name. All that was known about her for certain was that she was young, she appeared to be refined and educated, yet she could ride a horse and shoot a Winchester rifle, and she spent about ten years in the company of two of the most wanted bank robbers and criminals in the history of the American West. There were many rumors—that she was a prostitute, or a teacher, or both–but almost nothing could be confirmed. Even the Pinkerton’s Detective Agency was mystified by her.

On June 2, 1899, the Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy, and about five others, robbed their first train together—the Union Pacific—between Wilcox and Medicine Bow, Wyoming. They politely informed passengers and crew that no one’s lives were in danger as long as they cooperated. Then they blew up the mail car—using too much dynamite– and recovered $30,000 from the debris. On August 29, 1900, they took another Union Pacific train for $55,000. On September 19, $33,000, from a bank in Winnemucca, Nevada. The banks and railroads posted rewards of $10,000 a head for any member of the gang. In today’s terms, that would be over $100,000. Their $30,000 haul from the Union Pacific was probably worth about $400,000 today. Pocket change, by Michael Jordan standards.

Keep in mind that some conjecture is involved here. While it is known with some certainty that Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were associated with the gang known as the Wild Bunch during this period and that members of this gang committed a series of train and bank robberies during the late 1890’s and early 1900’s, everything else is somewhat conjectural. Naturally, the outlaws did not exactly keep detailed logs of their larcenies. Different combinations of men robbed different banks. In some cases, Butch or Sundance may have masterminded robberies that they did not directly take part in. In other cases, it is now known, robberies attributed to them were committed by others.

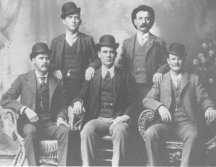

That fall, one of the gang members married a former prostitute, Lillie Davis, in Forth Worth, Texas. Lillie had worked in a well-known bordello named “Fanny Porter’s” in the rowdy Hells Half Acre—a sort of red-light district to which the authorities turned a blind eye, usually. After the reception, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and Harvey Logan, Ben Kilpatrick, and the groom, Will Carver, had a group portrait taken. This turned out to be a serious mistake, an act of hubris, by men who were otherwise regarded as very clever. A Well’s Fargo detective, recognizing Will Carver, obtained a copy of the picture and it was widely posted. Ironically, it may have been this picture, more than anything else, that sealed the image of glamour and sophistication attached to these men, in the public mind. The outlaws look dapper, bemused, and well-bred. They look like well-to-do bankers. They looked successful.

Study the photograph carefully for a minute. Will Carver was killed by a sheriff in Texas in April the next year. Logan, reputed to be the only genuine psychopath in the group, was killed (or committed suicide) in June 1904. Kilpatrick was captured and sentenced to 15 years in November, 1901. He was released in 1911, and killed while attempting to rob a train less than a year later.

Anyway, back in 1900, Cassidy and Sundance found their lives becoming difficult. The wild open plains of the west became dotted with towns and villages, new railroads and telegraph lines, marshals and posses, private detectives and bounty hunters. The legendary Pinkerton Detective Agency, hired by the railroads, was also hot on their trail. With their photos posted everywhere and large rewards for their capture, dead or alive, they faced long, lonely, restless lives as fugitives, never able to drop their guards for even a minute.

Oddly enough, they felt safe traveling to New York City with Etta in February, 1901. I would suppose they figured that would be one of the last places Pinkerton’s would expect to find them, but who knows?

After three weeks of rest and relaxation, they departed for South America, where they planned to go straight, buy themselves a ranch, and blend into the general population. Sundance, in particular, seemed to crave a “normal” life, perhaps hoping to settle down with Etta and raise children.

In South America, the threesome established a ranch near the remote town of Cholila, in southern Argentina, where they built a log cabin and acquired horses and cattle and entertained their neighbors and were regarded as good citizens. Argentine officials had no idea of who they really were. It is said that Etta even danced with the governor at a ball.

For unknown reasons, Sundance and Etta traveled to Manhattan on April 3, 1902 and remained there for three months. Butch accompanied them as far as Buenos Aires. He stayed in a comfortable hotel there, the Europa, for three weeks. Sundance may have sought medical treatment for a wound in the leg in Chicago, and Etta may have seen the doctor as well: about this time, the Pinkerton’s obtained a description of her. She was 5’ 5″, 110 pounds, medium dark hair, blue or grey eyes, no blemishes on her skin.

Butch allegedly said of her once, “She was a great housekeeper with the heart of a whore.”

Cholila was a remote village in Southern Argentina, inaccessible from the more settled north during the rainy season, and 15 days strenuous travel by horseback from Rawson, on the coast. Nevertheless, the Pinkertons were able to trace their movements through informants. They offered to arrest them and bring them back to the United States for trial, but the American Bankers Association was content to leave them alone in South America, where they wouldn’t be able to rob American banks.

The Pinkerton’s were not content. A spiteful agent, Frank Dimaio– it had to be spite, didn’t it?– circulated wanted posters in the area around Cholila. He tried to persuade the Argentine police that Butch and Sundance were involved with local bank robberies. By the end of 1904, the trio had disappeared from Cholila. They had been tipped off that the authorities were on their way to arrest them.

Without a source of honest income, Sundance and Butch fell back upon tried and true methods of survival. They robbed a bank in Rio Gallegos, near the Magellan Strait, and then they robbed one in Villa Mercedes, about 800 miles north of Cholila. It is generally believed that Etta took part in both robberies. According to friends, Butch and Sundance had wanted to go straight, but nobody would let them.

The details of the Rio Gallegos robbery provide an interesting glimpse of how they operated. The three arrived in town two weeks before the robbery and checked into the best hotel under assumed names. They deposited $12,000 in the Banco de la Nacion, the largest, most prestigious financial institution in town, and made the acquaintance of the manager and several tellers. They made it known that they were looking to buy some land and were invited to parties given by the elite of the town. Either Butch or Sundance dropped by at the bank every day, pretending to have business to discuss with the manager, while actually scrutinizing the layout, the schedules of major deposits, and the best escape routes. On the day before the robbery, they withdrew all their money, and threw a lavish party that lasted well into the night for all their new friends. The next day, at 11:00 a.m., one of them asked to see the manager while the other waited in the lobby. Then they pulled out their weapons, forced the manager to turn over the money, and raced off on fresh horses waiting for them outside, probably with Etta. They made off with $70,000. Several posses and police forces followed them for up to three weeks. All they found were tired, discarded horses.

In January 1906, the trio were seen crossing the Salado river on a raft, probably headed over the Andes into Chile. This may well have been the last reported sighting of Etta Place. She was never seen again in the company of Butch or Sundance, or, indeed, anyone else.

Percy Siebert, an engineer for the Concordia Mine, where Butch and Sundance worked for a time as payroll guards (!) claimed that Butch told him that Sundance had taken Etta back to Colorado for an appendectomy. While waiting for her to recover, Sundance got drunk one night, shot up his room, and had to leave town in a hurry. “He didn’t know what became of her after that,” said Percy. Nor did anyone else. Etta’s pretty, fine-featured face faded away into one of the great mysteries of the old west.

If she had needed an appendectomy, it would have made no sense to travel all the way to Colorado to have it done: she would have died well before she got there.

He didn’t know what became of her after that. I don’t want to just glibly pass over that line. If, as reported, Sundance fled the scene and never came back for her, it’s one of the saddest lines ever written. How does the “heart of a whore” break? Did Sundance grow tired of her company, or did she grow tired of their primitive, dangerous lives in Argentina?

In the following years, Butch and Sundance tried again to go straight, working for mines and ranchers, but inevitably their real identities were discovered and they were forced to flee. Again and again, they resorted to larceny to get by. After holding up the payroll for a mining company in Bolivia, in early November 1908, they stopped in a small, godforsaken little town called San Vicente. A citizen noticed the mining company brand on one of their mules and notified the local constabulary. When the soldiers arrived to question them, gunfire broke out. Butch and Sundance were trapped in a small, unprotected villa. After an intense gun-battle, both were seriously wounded. The police waited all night before confirming that the two were dead. Both of them had died from bullet wounds to the head. It was believed that Sundance shot the wounded Butch to put him out of his misery, and then himself.

There were persistent rumors that Butch survived the shootout—or wasn’t even there when it happened– and traveled back to the U.S. where he lived in anonymity for another thirty years. Unfortunately, there is very little convincing proof of this story. A Spokane machine shop owner named William T. Phillips famously claimed to be the former outlaw, but his claims have been demonstrated to be false.

What is clear is that no one ever heard from them again. All letters and contacts ceased as of November 6, 1908. And almost immediately, the process of transforming outlaws into icons set in. Western novels celebrated their skills with a gun, their rugged individuality, and “honor” code (the myth of the shootout at high noon, with it’s almost mystical adherence to protocol). One of the very first films ever made, Porter’s “The Great Train Robbery”, was inspired by their exploits.

* * *

Now most Americans nowadays seem to be possessed of this great notion that men and women who break the law should be punished very severely. If you commit a felony three times in California, the judge is obliged to sentence you to something like 50 years, under the “Three Strikes and You’re Out” laws passed by its enlightened state legislature.

You would think that a society that is so determined to punish crime that it would send pick-pockets, soft drug users, and shoplifters to prison for 50 years would regard a pair of bank robbers with at least a little ironic detachment. But a quick browse through the dozens of web sites devoted (and I mean devoted) to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid tells you a different story: Americans love these guys. They adore them. They admire them beyond all reason and common sense. They want to know everything about them, what they wore, what they ate, how many bullets they had in their gun belts at the moment they died. They want to believe that they were the fastest, the smartest, the best-looking criminals on the face of the earth. They are our heroes.

You could make an argument for it. Butch and Sundance planned their robberies with meticulous attention to timing and detail. Like Bonnie and Clyde, they seemed to rob institutions, not people. They tried to live up to a standard of professionalism. They preferred to get in and out quickly, with a minimum of confrontation. They studiously avoided shooting anybody if they could. This might strike the modern reader as chivalric, but there’s a lot of common sense to it too—murder is a far more serious crime than robbery, and would certainly draw more lawmen, detectives, and bounty hunters into the chase.

But when pursued and confronted, they would shoot to kill. I didn’t see many web sites devoted to the lawmen who died in their wake.

So you could argue that Butch and Sundance are heroes today because they were smart and witty and good-looking and didn’t really do any harm to people, other than to the banks and the corporations. On the other hand, you could probably say the same about a lot of those young men serving long prison terms in California right now. In 1993, 50% of the prison population consisted of people convicted of drug possession. Surely these men and women were no more intent on harming anyone—other than themselves– than Butch or Sundance were. I’ll bet a lot of them are witty. Some of them probably know how to dress well.

And you could say the same about a lot of young professional athletes, who get caught using drugs, or driving while drunk, or assaulting their coaches, or raping cheerleaders, or cheating on their college grades. Those poor boys. We should help them.

There is a further irony in the fact that one of the reasons Butch traveled out west in the first place was his thirst for adventure, slaked by cheap dime-store novels about the west. Blame the media.

It is important to remember that the line between right and wrong in the western frontier in the late 19th century was not clearly delineated. Ranchers frequently “employed” lawmen, to drive out homesteaders and “undesirables”. Sometimes the homesteaders would hire their own “lawman”, to fight the rancher’s lawman. State politics were exceedingly corrupt. Perhaps, like Bonnie and Clyde, the Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy represented the underdog, fighting the corrupt powers that be. Perhaps they were just good businessmen, like Monsieur Verdoux, doing what they had to to make a living. Kill someone during a robbery and you are a criminal. Kill thousands during an invasion and you get a medal.

But in the same sense, young black athletes, like Allen Iverson, Lattrell Sprewell, and others, emerged from poverty and economic oppression in the dark inner cities of America, to represent vicarious triumph over the corrupt, rich, white racist establishment.

There’s not much out there that reads well in black and white. Most of the world is as grey as Etta’s peerless face in that wonderful black and white photograph. We don’t know what became of her after that.