When I did a search for a philosophy professor I took a course with 40 years ago at Trinity Christian College, I found nothing. Except for one indirect reference. [I have since located an actual article by Dr. Vrieze, in the digital collections of Dordt College.]

This is shocking to me. Can a man devote so large part of his life to teaching philosophy to hundreds of students and disappear with barely a trace on the Internet? Well, of course, he did all this long before the Internet even existed, but still, you would think there would be a few pages somewhere honoring his legacy, the hundreds of students who were inspired (or not) by his lectures. Maybe some former student fondly remembers the required perspectives courses we all had to take our first year at Trinity (What is this? A chair? How you know it’s a chair and not an umbrella?)

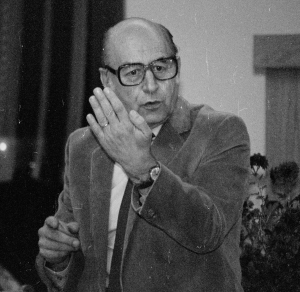

Here is my note on Dr. Maartin Vrieze, so there is at least one page somewhere devoted to him:

2 plus 2 does not Equal 4

Probably the best course I took at Trinity was Dr. Vrieze’s “Philosophy of Science” class.

Until then, we had studied philosophy in various eras, medieval, modern, 19th Century. We studied Kant and Descartes and Hume, all relics of a different era, relevant but quaintly insular. Who really cares about Kant’s categories of being in the era of Woodstock and Watergate and Viet Nam and Bob Dylan and the Beatles?

The revolutionary aspect of the Philosophy of Science course was it’s reliance on current, living philosophers, and the course texts consisted mostly of periodicals instead of text books. It was here I was introduced to Karl Popper, Imre Lakatos, Paul Feyerabend, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. And it was here, for the first time, I was convinced that 2 plus 2 might not equal 4. This mathematical equation was not some transcendent logic that would always be true no matter what you believed about God or reality or physics. It was the product of rigid doctrines promulgated first by the Greeks, and sustained through millennia by everyone from Thomas Aquinas to Immanuel Kant.

To be clear, I didn’t necessarily believe that 2 plus 2 was a subjective idea that could be discarded at will. I was skeptical of that too. But my readings, especially of Feyerabend and Lakatos and Wittgenstein, convinced me that you could make an argument for the idea that it really was an arbitrary construct based on assumptions about the nature of physical reality, and that if you assumed a different nature of reality— say, for example, that time is a river, not sequence of discrete events— you could end up with a universe in which 2 plus 2 does not equal 4.

Karl Popper presented the idea of paradigms: that we can understand the world as the framework of a model or set of assumptions which endure as long as they are “useful” and productive in some way. This idea has been useful to me over and over again: look at the people who support Donald Trump. They operate according to a different paradigm. And it is almost impossible to shift someone’s paradigm until it begins to break down or disintegrate under them, or until they find a new paradigm that is more “useful” to them, that makes more sense to them, and seems to.

Wittgenstein believed that all of reality is essentially the product of language. It was in linguistic expression itself that our experience of the world is constructed. I found this idea very intriguing.

Mark Vandervennen, who was in the course with me, kept asking, “what is the Christian response to these philosophies? How do we answer them with our own truth?” Until then, every course on philosophy at Trinity concluded with a survey of the “correct” Christian response to these pagan ideas. Most of the time, this consisted of nominally Christian thinkers like Herman Dooyeweerd who rather obviously adapted Kant’s model of knowledge into his own scheme, in Dooyeweerd’s case, particularly, categories of being.

Vrieze steadfastly refused to provide an out. He would sometimes repeat the question to the class: “How do we respond to Wittgenstein? Tell me.”

I began to believe that this course was Vrieze’s revenge on the entire edifice of Christian College philosophy and theology. He seemed to be demonstrating to me that none of the pat answers we received in all of our earlier perspective and philosophy courses were adequate to address the real issues raised by the most powerful living philosophers.

Perhaps he was addressing his own professional disappointments. He never seemed to have risen to a position of prestige or professional recognition that I think he felt he deserved. His European sophistication (he was born in Holland and studied in South Africa) seemed out of place at a mid-western American Christian college.

Google Dr. Maartin Vrieze. It is shocking to me that there is almost no references to him on the Internet. How can a man devote his life to a discipline like philosophy and not leave at least some trace of his work on the internet, even if his career was before the internet?

I need to do a page and make the link: someone should have a tribute to this gregarious, entertaining, provocative teacher.