Pantages Theatre, Toronto, April 23, 2001

“Cabaret”, after all, is still a musical.

You know– those dippy concoctions in which impossibly handsome lumberjacks sing schmaltzy love songs to dainty girls with kerchiefs in their hair while throwing them over hay stacks and pitch-forking in unison. Absurdities, in other words. Something which, in the right context, could be mistaken for a parody of something that is stupid it couldn’t possible exist in an original form.

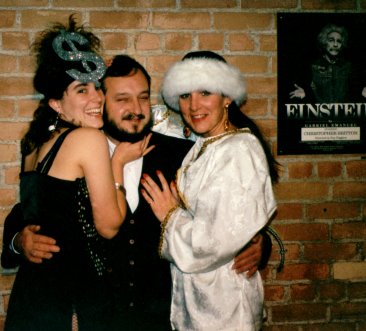

The author with two members of the “Cabaret” cast, Theatre Kent, Chatham, Ontario (1992).

(Photos from 1992 Theatre Kent production of Cabaret, Chatham, On.)

Yes, you heard it here first: the musical is no more of an “art form” than ceramics or collectible dolls or the can-can.

So Cabaret is still a musical, and so, at some point, Sally Bowles sings a dippy love song about this man (Cliff) just maybe being the one who will turn out to be “different” from all the other one-night stands, and might be that one special person with whom she can build an enduring relationship and it’s obviously a showpiece number, and the audience is expected to applaud at the end of the song even though it occurs in the middle of what is supposed to be a play, a story, a narrative, and even though the guy is gay.

By the way– I have to rant about this for a moment– the theatrical tradition of applauding at the end of a musical number within a theatrical performance is absolutely disgusting, contemptible, idiotic, annoying, and stupid. I hate it. If the drama is worth watching, the last thing in the world you want is for the audience to suddenly break out into applause. The drama is supposed to flow from scene to scene. Contrasts and ironies are developed and intensified. Emotions are pitched. Characters are illuminated. But, suddenly: hey, great singing there Alphonso! Bravo! What a show-stopper! Now, what was the girl doing with the rope around her neck?

Most musicals– however– deserve the interruptions. They are mostly pabulum, bland confections of trite melodic ditties.

“Cabaret” is not trite. It’s a very acute, perceptive dissection of the critical period in German history.

But the audience was trained: they applauded after every song.

Now, in all fairness, most of the singing in Cabaret takes place in the Kit-Kat club, so the applause is not as disruptive as it is for, say, “The Sound of Music”, wherein we all applaud the children going to their bedrooms, or a nun dancing on what is supposed to be a hillside.

As I said, for most musicals– a phony art form if ever there was one– the applause at the end of each song is not really a problem because I never hear it because I rarely go to musicals. Do I really want to see “Oklahoma”? No. Do I think “The Sound of Music” really illuminates the nature of the Nazi terror? Not a chance. Does “Oliver” move me to some kind of state of contemplative bliss? Oh, please…

For the record, I have seen some musicals, live, on-stage, as well as a few on film. Here’s a list that I can remember off-hand:

- Oklahoma (so very weird)

- The Producers (delicious and funny, because it mocks the musical)

- The Sound of Music (compared to “Cabaret”)

- Fiddler on the Roof (least bad of this lot)

- Cabaret (a twisted work of dark genius)

- Hair (a musical with pseudo-rock songs in it. The Milos Forman movie version is interesting.)

- Oliver (can’t remember)

- Showboat (boring, sorry.)

- Camelot (awful)

- West Side Story (Natalie Wood’s vocals were recorded by Marni Nixon– need I say anything more about phoniness?)

- South Pacific (dumb, dumb, dumb)

- My Fair Lady (who cares)

I have also seen and enjoyed “Jesus Christ Superstar” live and on film, and “Evita” on film, but neither of these are really musicals. They are operas. The word “opera” is death at the box office, so they are advertised as “musicals”. Get it straight: “Jesus Christ Superstar” is an opera, in form and style and design. It has arias and recitatives and the entire narrative is contained in the songs. It is an OPERA. And so is “Evita”.

(Backstage)

Anyway, back to “Cabaret”. “Cabaret” is loosely based on a book by Christopher Isherwood that is a fictionalization of his life in Berlin during the rise of the Nazis. It’s really not a very good book. It’s interesting, and it’s not awful, but it’s not great literature. But he did create some memorable characters and we don’t really have very much good English writing on Berlin in the 1920’s or 30’s so it stands out. In 1951, a guy named John Van Druten thought so too and wrote a drama (not a musical) based on the stories and it was produced on Broadway with Julie Harris and it was deemed a success. In the 1960’s, Hal Prince decided to develop it into a musical and recruited a couple of guys named John Kander and Fred Ebb to create the songs. Joel Grey created an absolutely unforgettable “Emcee”, and in 1966 the Broadway production won 8 Tony awards including “Best Musical”. In 1972, Bob Fosse made it into an exceptionally good film– except for the awful casting of Peter York as “Cliff” and Liza Minnelli as Sally Bowles– which won numerous Oscars including “Best Director”. Joel Grey indispensably reprised his role as the Emcee.

The production I saw live at the Pantages was “directed” by Sam Mendes, who directed the film “American Beauty”. Did Sam Mendes actually direct this version? I doubt it. More likely, this staging of Cabaret was based on his original staging, but directed by Rob Marshall.

Now, odd things happen to brilliant talents in our culture. We live in a democratic, free society. The powers that be do not censor our literature or movies or theatre. That means, in theory, that you can say anything you want in a play or movie or book, and no one will arrest you and prevent people from seeing or reading what you have to say.

No. But we go one better: when someone presents a disagreeable message to us, a message that might imply that there are faults or sins or crimes in the way we– the collective “we”, the audience– act, we simply appropriate the message, repackage it, and make it into a cultural artifact.

Consider, if you will, the title song of “Cabaret”.

What good is sitting alone in your room?

Come hear the music play,

Life is a cabaret, old chum,

Come to the cabaret

A line from this song– “What good is sitting alone in your room”– has been appropriated by SFX productions for the advertising of the touring version of “Cabaret”. Obviously it means, in this context, don’t stay home watching television or playing cards or staring discontentedly at your spouse! Get up off your fat duff, whip out your credit card, and fork over $80 for a crummy seat at a large theatre and watch our packaged presentation of a musical that collected amazing critical reviews and therefore must be artistic and telling your friends you saw it will confirm your good taste. Get out! Have a great time! Make it dinner and a show, and stay overnight at the Ramada with the pool and sauna and calypso bar! Enjoy yourself! Live!

The trouble is, that’s not what the song means at all. In the context of the play, Sally is announcing her refusal to accept reality, or any kind of responsibility for the monumental evil that is closing in around her. When Cliff announces his disgust with the Nazis, Sally says, “but what has politics to do with us?” Cliff tells her that she is blind. And the play tells us that this diseased society– Berlin of the 1930’s– has opened itself to the infusion of Nazi ideals. And Sally blithely sings on, “life is a cabaret, old chum…” Is this the sentiment the audience wishes to identify with?

I grant you– the advertising itself might be playing with irony. But I doubt it.

In the original production by Hal Prince, another line did cause consternation. The Emcee does a little dance with a gorilla, while singing to the audience that, if they could only see her through his eyes, they would realize how beautiful and desirable she was. At the end of the song, he sings,

if you could see her through my eyes/

she wouldn’t look Jewish at all.

It’s a terrific line. It’s a fabulous line. It’s the entire heart and soul of the play’s anti-nazi sentiment. And it was rejected by the original producers and deleted from the production! Why? Because they thought it would imply that the play’s producers thought that Jews resembled gorillas? Yes. They thought Jewish Theatre-goers would be offended by it!

I am sometimes filled with wonder at this crazy world of ours.

Cabaret is a “concept musical”. That is, instead of lumberjacks singing to virginal maidens while dancing through the fields, the trees themselves sing. Just kidding. I mean that there is never any pretense that the music pops out of real-life situations into a tiny set-piece before the drama resumes. In “Cabaret”, the music is organically and symbolically linked to the drama, and becomes a metaphorical part of the narrative. The Emcee, for example, often intrudes on the action, singing a line, or, through facial expression, passing ironic judgment on the characters.

Ah… but in this new production, the Emcee has also changed.

In the original, Joel Grey was a magnetic, ambiguous personality. He invites you in to the Kit-Kat Klub, to leave your troubles outside and live for the moment. He urges you to enjoy life to it’s fullest without inhibition or hesitation. The ambiguity in this part is critical: he is simultaneously attractive and repulsive. He glowers and caresses, cajoles and demands. He is sexually ambiguous too– androgynous, asexual, an object of fantasy or domination. One minute he is rhapsodizing about the pleasures of a ménage a trois, the next he is a menacing storm trooper, winking to the audience– this is a game we all can play. The swastikas, the leather, the boots mean nothing. It is just another fetish. Grey’s performance is the richest, most entrancing element of the movie version, precisely because he doesn’t offer the viewer any shortcuts or simplified perspectives. While the owners of the club are beaten to a pulp by Nazi thugs, the camera cuts back to Grey, leering, laughing, chasing the cabaret girls in their lacey underwear. We’re all part of it…

In the current touring stage version of Cabaret, the Emcee looks more like Edward Scissorshands. He is pale, intoxicated, and diminished. He is, in the words of Joe Masteroff (author of the book of the original version), a “figure of doom”. During the first performance of “Tomorrow Belongs to Me”, the sinister anthem to the rising power of the disciplined Nazis, the Emcee bares his ass: it has a swastika painted on it.

The audience can relax: evil has been conspicuously labeled and we are inoculated against the seductiveness of it all.

Which brings to me a certain ambiguity at the heart of “Cabaret”. You have a number of likeable characters at the center of the story who indulge in various degrees of licentious behavior and then you have the big bad Nazis trampling through the scenery hauling everyone off, presumably, to concentration camps. I’m not sure we want to draw a moral from the story, but if we did, what would it be? Isherwood was gay, so surely he wouldn’t want to have suggested that sexual immorality– defined in the broad strokes of the KitKat Klub– leads, as a consequence, to repressive, authoritarian governments? Cliff (or Brian, in the movie) leaves Berlin because he sees the Nazis as a genuine threat while Sally is blind to them. So he has “come to his senses”. So he goes back to America where he could be arrested for having sex with another man, and where plays like “Cabaret” have to conceal the homosexuality of one of it’s lead characters in order to find an audience on Broadway.

It’s a neat ambiguity. But then, Isherwood always insisted that his perspective was that of a camera– recording, but not judging.

Conversely, the orchestra is now comprised of beautiful women. In the original, the orchestra consisted of lumpy middle-aged men garishly dressed as women. Why the change? I don’t know. The first view of the orchestra in the film version is quite shocking, disturbing. How far will people go in this place? What is this Emcee leading us into? Is there any sanity in this place?

The Toronto production is smooth and efficient and even somewhat elegant. The orchestra is extremely tight and well-mannered, though the New York Times reported that the original revival production tried to sound more “authentic” and raw, as a real orchestra in the real original clubs would have sounded.

Christopher Isherwood lived in Berlin between 1930 and 1933. He wrote, of course, but paid the bills with English lessons. It was here that he met Jean Ross and the other persons who inspired the character sketches of “I am a Camera”. Isherwood later moved to the United States and taught English and wrote screenplays in California. “I am a Camera” was not a great success until the dramatization by John Van Druten made it’s mark in the 1950’s. In this version, as in the later movie, Cliff Bradshaw’s homosexuality was downplayed.

A book inscribed to “Jean Ross”, from Christopher Isherwood himself, was recently offered for auction at $12,500 by James S. Jaffe Rare Books.

Hal Prince on the movie version of Evita:

I must say I think that’s where the movie failed for me. They didn’t take that into account. They didn’t bother to figure out what was behind its underpinnings in the first place – and JUST told the story.

Did you like “The Money Song”? I did too. One of the highlights of the show. But it wasn’t written for the original “Cabaret”. It was created for the film version. But wait– you saw it in a live production?! Dang right. The movies rule! After the success of the Bob Fosse film, the stage version incorporated “The Money Song” too. Cross fertilization? Or homogenization?

Movies rule? Bill, check yourself. According to Hal Prince, the returns on “Phantom” are far greater than the total returns on the movie “Titanic”. Why? Because “Phantom” has played to sold-out houses for 11 years at, like, $45 a pop, whereas “Titanic” played to sold-out houses for three months at about $8 a pop. Hal Prince reports meeting people who have seen “Phantom” 75 times. He thinks that’s great. I’m not sure I don’t think it’s sick. What kind of person, do you think, sees “Phantom” 75 times? Think about it.

In it’s first incarnation, the German officers in “The Sound of Music” did not wear swastikas.

We now believe, in fact, that it is one of the great terrible illusions that we create an automatic redemption in such events as the Nazi era. Dr. James Young, Professor of English and Judaic Studies, University of Mass.