Martin Heidegger (“Being and Time”) often reads like a parody of philosophy. The first 35 pages are replete with repetitive (in my opinion) insistences that before you can analyze reality in any sense you must apprehend the being-ness of being there in the radical sense of existential being, which everybody else has failed to do.

I consider the idea that Heidegger may be a massive fraud. I think it’s a possibility. He is very, very esteemed in the world of cool philosophy geeks, but it is quite possible that they are entranced by Heidegger’s incomprehensibility being confused for “mystique”, combined with the language that is almost poetically inane. “The being of being is the beingness of not-being authentically in a non-thematic ontological context that cannot be known.” Ok. I made that up– but it’s close.

It is quite possible that he has hit upon something that everybody already knows in a certain valid sense and has taken to describing it as if it is hidden from everyone else and must be revealed to them. Don’t you see that we are all breathing?! We’re all sucking air in and out of our lungs! This has profound implications for all of life. Read him long enough and you begin to think about your breathing. Maybe you try breathing differently. Two exhales for every inhale. Try breathing through one nostril at a time. What if I stop breathing? By golly, he’s right: breathing is incredibly important. We all need to think about breathing.

He is his own best argument for Wittgenstein’s argument that the world is comprised entirely of facts. What we believe to be reality is always and only a construct of the language we use to express our experience of it. How does Heidegger know that everyone else does not know what he knows about being? He offers no explanation. He only knows the language that others have used to describe time and existence and phenomena but he really has no explanation of how he can possibly know that the way this language is used is inadequate to explain the authentic meaning of being.

He seems at times to assume we have a reason for believing there are others in the world, yet I have not seen the slightest discussion of the senses through which we experience others, and the world itself. He seems to insist that we cannot really know if they have a real existence outside of our imagination, just as he doesn’t seem to be concerned about how time can be explained if we only barely understand the meaning of our own “being there” or Dasein. Is time linear? Is time atomic? Is time continuous? I’m at page 113. I’ll let you know if I find an answer.

According to Heidegger, Western Philosophy has it all wrong because it has skipped the most essential truth which is that “being” itself, or “being there”, or “Dasein”, is the proper subject of philosophy and has been almost entirely ignored, at least, since the Greeks. He is going to rescue us from this terrible omission. Get out of your car, burn your records and books, change your diet and haircut: we have no way to experience the world. Being there.

Let’s get this out of the way right from the start: Heidegger believes that Western Philosophy has forgotten the essential character of “Dasein” but what it is it has forgotten, he can’t seem to remember.

There it is. I summed up Heidegger that way at Trinity Christian College 45 years ago and I stand by it.

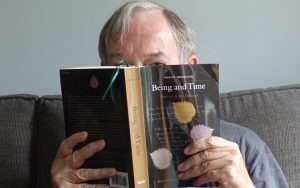

What prompted this reflection is my reckless urge to revisit “Being and Time” now that I have experienced a lot more of both. I am in my 60’s and haven’t looked at this book since I was in a philosophy course taught by Dr. John Roose at Trinity Christian College in Palos Heights, Illinois, back in 1973. It is the only course I ever took anywhere which I did not complete, and for which I received an “F”. It wasn’t the difficulty: “Contemporary Philosophy” taught by Dr. Vrieze was far more challenging– and satisfying– and of course I did well in it. I still remember a considerable chunk of that course, on Paul Feyerabend, Imre Lakatos, Karl Popper, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and others. Feyerabend was the first philosopher I read that convinced me that it actually was possible for 2 x 2 to not equal 4. And Karl Popper’s discussions of paradigms is still very useful to me.

But here’s a line from Martin Heidegger that I think you might find as amusing as I do (from “Being and Time”, translated by Joan Stambaugh, page 35):

Because phenomenon in the phenomenological understanding is always just what constitutes being, and furthermore because being is always the being of beings , we must first of all bring beings themselves forward in the right way, if we are to have any prospect of exposing being.

In regard to Kant, one question that remains: if we can never know a thing in itself– only our empirical experience of that object– does it matter? If we can never know the thing in itself, then, really, does it even exist? And so if Heidegger insists that we don’t apprehend Dasein– being itself– does it even exist? More critically, does it matter? Heidegger seems to believe that we can encounter Dasein if we cast off our archaic beliefs. This makes him a superman, since he is the only one who knows about Dasein and he is here to enlighten us. (In fairness, he does credit some other philosophers– even Kant– with having a diminished idea of Dasein). But again, given his explanations of how we are ignorant of the decisive importance of Dasein, how can he possibly know anything about others’ experience of it?

All this so far and I haven’t even mentioned that Heidegger was a Nazi.