“Joan Crawford would have killed to play her. ” NY Times, on “Black Swan”.

And noted: “Dancers often spend more of their time in front of the mirror than before an audience”.

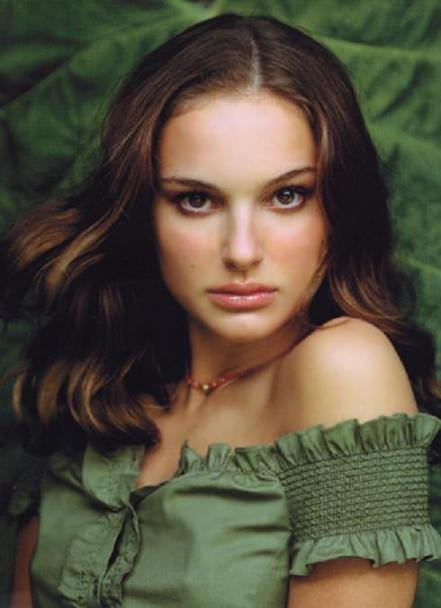

Okay– first of all I do want to say this: I think Natalie Portman is one of the most enlightened, smartest actresses working today. You may not want to see her as inspiration for your acting technique, but she is model of wisdom in every other respect. I’m not kidding– check out what she does and says in her non-Hollywood life. She’s very, very wise.

I’m going to add to that– Natalie Portman is at a priceless, searing stage of her life. She is smart enough to perceive the twisted effects of celebrity (the perverse obsession with her role in “Leon: The Professional” for example and the sexualization of her image as a boyish naïf from all of her movies), but not old enough yet to resign herself to it. She expects better. But she is pleasingly reflective and down to earth and astute and it will be sad when she stops commenting on it and it becomes a part of her permanent emotional armour and we will have lost something.

However…

The biggest problem with “Black Swan” is that director Darren Aronovsky and star Natalie Portman– who, by the way, is really a terrible actress– never really shows you the payoff: a talented dancer at work. They don’t know how. Watch fifteen minutes of Mike Leigh’s “Topsy Turvey”, or even “The Red Shoes”, and then try to tell me it’s not possible. It absolutely is. “The Black Swan”, in fact, makes the worst mistake a movie of this type can make: it wallows in the suffering without even hinting at the reward, and in this kind of narrative, the only satisfactory explanation for the suffering– aside from pure monotonous psychosis– is the glory of the reward.

Just one example: at one point the director threatens to take the role away from Nina because she hasn’t demonstrated sufficient passion (which, cringingly, is linked to the director’s sexual fantasies). We are left clueless about just how wrenching, in real life, a decision like that would be. We are left with the impression of a parent threatening to take dessert away from a child if she doesn’t do her homework. We are left with the impression that the director actually chose, as his star of this production, someone he clearly believes is incapable of performing it.

It’s not really like he realizes he made a mistake. It’s like this: the viewer realizes that the director could never really had a good reason for choosing her in the first place, and the story loses all sense of believability.

We are left with the impression that someone else could just step into the role, precisely the opposite of what the director thinks the audience will think as Natalie Portman crinkles her face unpleasantly and weeps to tell us instead how much she suffers for her art.

I’ve said it before– the rule about showing a believable drunken man is to produce a man trying (and failing) to stand straight– not someone trying to look like he is falling over. Natalie Portman, for 90 minutes, looks like she’s trying to fall apart.

Joan Crawford or Bette Davis could have played this.

Why was Leslie Manville from “Another Year” not nominated for a “Best Supporting Actress” Oscar? Well, aside from the obvious– no powerful Hollywood machinery working on her behalf to get her the nomination– well… that’s about it. That’s why she doesn’t get the nomination. That’s why so many mediocre actors and actresses do get nominated.

So when Natalie Portman gets all tearful in a few weeks, convinced that her peers really chose her for this award, for her acting, for her dedication, for her unremarkable impersonation of a ballet dancer in a few select shots…. think about that last shot of Leslie Manville in “Another Year” realizing that whatever it is Tom and Geri have…. she doesn’t.

That is, simply, truly great acting– not the showy pseudo-method business that wins you Oscars.