Crumbs

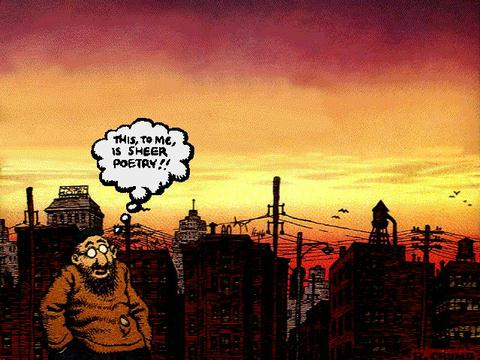

Robert Crumb is famous for a number of cartoons he created in the 1960’s and 70’s, the most celebrated of which was the Keep on Truckin’ schematic, which became a trademark of sorts to the Grateful Dead. He is also the originator of the Fritz the Cat character, which became the subject of a full-length x-rated movie by Ralph Bakshi. Crumb disapproved of the movie.

In 1994, Terry Zwigoff, a friend of Robert’s, made a disturbing, brilliant documentary called Crumb, about Robert, and his two brothers, Charles and Maxon. (Crumb’s sisters declined to take part in the film. You may wonder about that by the end of the film.)

I say “disturbing”. Searing might be more like it. The Crumb brothers pull no punches. At times, you almost can’t believe they are saying the things they say on camera. Don’t they realize how shocking they are? Yet this is no television talk show. The brothers are never coy or evasive, and don’t really shift blame away from themselves, or try to cast themselves as unwitting victims. If there is one attractive quality about these brothers, it’s their honesty and their sense of personal responsibility.

Crumb’s father was brutally strict, and his mother over-compensated, and the three boys had some kind of weird chemistry going. From the time they were little, they became obsessively fascinated with comic books. They were extremely gifted at drawing and Robert even organized the three brothers into a production company and they created their own variations on Treasure Island.

All three were also severely socially dysfunctional. Charles, though in his forties, lives at home with his mother, almost never leaves the apartment, rarely bathes, and uses prescription drugs to keep from becoming “homicidally disturbed”. According to Robert and Maxon, he has never had a sexual relationship with anyone but himself. He had made several suicide attempts before the documentary was made, and, a year afterwards, finally succeeded, providing the film with a poignant postscript.

[Update 2022: read that paragraph now, it occurs to me that a big part of Charles’ troubles may have been the side-effect of the prescription drugs. If he stopped taking them at any time, the effects of withdrawal would have produced “symptoms” that would like be attributed to his personality, instead of to the drugs themselves and the effects of withdrawal.]

Maxon lives alone in an apartment and has been arrested several times for sexual assault. He swallows a long length of cotton cloth every three weeks to cleanse his bowels, feeding it like string slowly into his mouth, and likes to sit on a bed of nails and meditate. Like Charles, he is, frankly, a slob. He describes, with helpless amusement, how he followed a girl wearing tight shorts into a drug store and could not resist the urge to pull them down while she was waiting in line at the checkout. Unlike Clinton, there is no evasion, no excuses, no hypocrisy. He confesses to a repugnant act, but you almost like him.

Robert, who at first appears to be seriously maladjusted, eventually emerges as the sanest of the three. He manages to make a living from his drawings, develops relationships with women, marries, divorces, marries again. He has two children, years apart, one by each wife. Yet you can see that he’s not too far removed from Maxon and Charles. The difference may be that Robert succeeded in transferring his anti-social impulses into his art.

Crumb is one of the most brutally honest documentaries you are likely to ever see. The three brothers talk openly about their father’s abusive discipline, their sexual preferences and fetishes, their own hopeless perspectives on themselves and each other. Robert’s comics have always been controversial, and the film includes interviews with editors and fellow cartoonists who express their own misgivings about some of his more controversial stories. In one, for example, two characters enjoy the sexual favours of a woman with no head. They consider her perfect, since they don’t have to make conversation with her afterwards. In another, an outwardly normal, All-American family, is actually rife with incest. An editor allows that she is not sure that Crumb actually disapproves of the incest. A third example is a parody of consumerism, describing a new canned meat product called “Niggerhearts”.

When challenged, Robert Crumb, like his brothers, is not very evasive, arrogant, or apologetic. Who knows, he seems to say. Maybe I should be locked up. I don’t know why I have to draw those things but I do. They’re in me. Implied, of course, is the idea that many of these ideas are in us as well. Considering the number of awards this documentary has garnered, you would have to admit that many critics and film-goers acknowledge this. How else could you stomach such a man, or a film about this man?

It is unclear, at times, whether Crumb is parodying himself or society in general or those who think they understand society. His stories are hardly simple parables.

Another example: a black woman is convinced by several businessmen that performing degrading acts will make her a superior human being. She doesn’t outsmart them, though she realizes she’s being put on. Some readers interpret this to mean that Crumb thinks she is as foolish as the white businessmen think she is. Or is this a parody of the businessmen, and the way they attempt to turn even social oppression into material advantage? Or is it an assertion that materialism is itself the most oppressive force in our society? (I favour the last one).

Is it a sin to be truthful? Only if your truth is different from everyone else’s. Is our society ready to admit that otherwise “decent” people can harbour obscene fantasies or racist beliefs? Is our society ready to admit that even victims can be stupid?

I don’t think we are. It’s too difficult. We are far more comfortable believing that blacks are inferior and that women suffocate men or that blacks are innocent victims of racism and that women are morally better than men. We don’t like being thrown a curve. But remember that the most powerful abolitionist tract of the 19th century was Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Today, even black activists are mostly contemptuous of its simple-minded moralism’s. Why? Because someone like James Baldwin had the nerve to attack one of the most sacred icons of progressive and religious humanism in existence. And you know what? He was right.

So is Crumb merely ahead of his time?

Well, what really is outrageous nowadays? I think it is obvious that some of our values are completely screwed up. We find the Clinton-Lewinsky affair outrageous, but not the deaths of tens of thousands of Moslem Serbs. We are outraged by a school boy killing his class-mates with a high-powered rifle, but not by an organization that spends $80 million a year to promote unrestricted access to every kind of weapon imaginable. We are outraged by a school teacher who has sex with a Grade 6 student, but not by a talk show host (Larry King) who has been married five times. We are outraged by someone who clubs a gas station attendant over the head to steal $15, but not by a securities seller who rips his clients off for a billion dollars. We are outraged at a seventeen-year-old kid who breaks into houses to steal money to feed his drug habit, but not a pharmaceutical industry that is doing its level best to make us all dependent on drugs. We are outraged at Mexicans crossing the border to seek a better life in the U.S., but not at the economic imperialism that turns self-sufficient Central American economies into impoverished coffee growers for Starbucks. We are outraged when the United Nations wants to include the U.S. among the nations accountable for war crimes to a new World Court, but not when Congress continues to subsidize an Israeli government that denies the most fundamental human rights to its own Palestinian population. We are outraged when a protester burns a U.S. flag, but not when U.S. negotiators refuse to believe that fish stocks on the west coast are in danger of extinction if over-fishing continues. We are outraged when an artist puts a crucifix into a jar full of urine, but not when the record companies routinely cheat artists out of the royalties they are due by jiggering their accounting records. We are outraged by a doctor who helps terminally ill patients die without pain and in dignity, but not by doctors that routinely recommend expensive and useless surgeries to elderly patients who are likely to die within months anyway. We are outraged by cloned sheep, but not by attempts by corporations to patent human DNA sequences. We are outraged by homosexuals seeking benefit coverage for their partners, but not by the fact that we are denying AIDS treatments to impoverished African nations to protect our own patent rights.

What exactly determines our outrage? What is it that most excites us about someone else’s sin? Isn’t it probable that when we proclaim our outrage, especially when we do it in the strongest possible words, we thereby hope to impress others with our own purity, and deflect suspicion away from ourselves? Since no one suspects us of murdering children in Rwanda or robbing old women of their lives’ savings, we don’t get too excited about those crimes. But if someone were to suspect us of sexually harassing an attractive secretary…. well, we’ve probably had a thought or two about it, haven’t we?

What is most telling about this analysis is not that we seem to be so defensive about certain human failings. It’s that the human race, in general, doesn’t really care all that much about starving children or ethnic cleansing or torture or exploitation. We really don’t. But we badly need to pretend that we are virtuous, so, by common consent, we identify certain transgressions as worthy of our hysteria. We draw lines in the sand, and then go ballistic when someone crosses one of them.

I don’t really like Robert Crumb. At best, he is a maladjusted misogynistic misanthrope. But he is articulate and honest, and his cartoons are the work of a genius. There is a soft underbelly to American public morality, and Crumb pokes a sharper stick at this underbelly than anyone else.