I never liked Norman Rockwell paintings. They had this kind of smug middle-American arrogance to them. Every one of them seemed to shout at the viewer: “Why would anyone in the world live other than we as Americans live? We’re so great!” They are the most purely American of artifacts. They idealize conservative American values: church, boy scouts, the military. In a portrait of a citizen speaking out at a city hall meeting, Rockwell seems to say, yes, in America, the average citizen has a say in the way things are run around here. Right. The average citizen and the Fortune 500 and the military industrial complex and Rush Limbaugh. But I’ll bet that guy speaking up at that meeting got his parking ticket reversed.

Later in life, however, he began to turn out works that actually alluded to real problems in the real world: “The Problem We all Live With” shows a black girl about to enter a segregated school, surrounded by marshals, whose faces we cannot see. Very moving. Politically correct, of course. But artists are supposed to be visionaries. They’re supposed to be true to a powerful inner voice tell them that this is the way things are no matter what anybody else says. Rockwell was not exactly ahead of the curve here: he did his painting in 1964. Even the U.S. Federal Government was on-board by then.

Norman Rockwell died in 1978 at 84.

There have always been those who argue that Rockwell was a GREAT artist who belongs in the company of Picasso, Millet, Miro, Pollock, or maybe even Andy Warhol (ha ha). Why, they ask, should an artist be held in contempt, just because he is popular? We need to revise our opinion of Rockwell. We need to put his “Fixing a Flat” right up there on display next to Bacon’s “Man in a Box” and Monet’s “Lily pads #4,378”. .

Well, people can revise their opinions of anything they want. Sometimes, when the obvious has been with us for so long, and for good reason, it becomes fashionable to assert that the obvious was never true. William F. Buckley Jr. decides that “Tail-Gunner” Joseph McCarthy was a hero after all. William Goldman decides that John Lennon was a jerk. Everyone is supposed to go: oh! How brilliant! He saw what everyone else missed! Rockwell really is a brilliant artist!

The thing is, sometimes things are obviously true because they are, well, obviously true. Anyone who has seen the video tape of McCarthy holding a hand over a microphone and smirking while whispering to his aide, Roy Cohn, surely suspects that the man was an idiot. And anyone who has tape of John Lennon talking to reporters from his “bed-in for peace” knows that he was a lovable idealist who wished harm to no one and was far less foolish than he appeared.

But Rockwell a great artist?

No, he isn’t. He is a great illustrator. But you can’t be a great artist if you are constantly pandering to your audience. Rockwell clearly selected subjects and meanings that he knew his audience would accept, adore, and admire, and he presented these subjects and meanings in an idiom that was utterly conventional. Here you are: you imagine that Americans, in the late 20th century, still go down to the fishing hole, or stop at the side of the road to skinny dip on a hot day, or glance with awed respect at little old ladies who pray before they eat their meals in a restaurant. Dream on. These are popular images because they appeal to people’s illusions about themselves. That’s not art. That is propaganda.

It somehow doesn’t surprise that Rockwell did also did advertisements for Crest and Jell-O and other companies. I don’t think Rockwell was embarrassed. Why should he be? He was an illustrator.

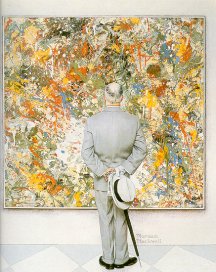

Rockwell himself certainly believed he was an important artist. He did a painting of a man standing in an art gallery staring at a Jackson Pollock splatter

painting.

painting.

You can’t see the face but you can picture the quizzical expression from the body language. The man is fair: he’s giving the painting a chance. He’s staring at it, trying to understand it. But you know and I know that the painting makes no sense to him. And that, to Rockwell, is all that there is to modern art.

Rockwell seemed proud of the fact that he was able to credibly, he thought, recreate the Pollock painting himself, using the celebrated splatter technique. Nothing to it. I could paint like that if I wanted to.

Well, I kind of agree with him. Abstract art, or non-figurative art, or whatever you want to call it, has followed it’s own course into oblivion and self-parody. It has become an industry of critics, painters, galleries, art teachers, and students, all trying to define the absurd, all attempting to establish themselves as authorities or experts on something that ridicules expertise and authority.

But I’m not ready to say that the public is right either. Rockwell isn’t the only figurative painter in the world. Van Gogh, Rembrandt, Delacroix, Michelangelo, Da Vinci, Boticelli, Van Eyk, and even Picasso, were all figurative painters at one point or another, but it’s not hard to see that there is a substantial difference between their work and Rockwell’s.

And the public never accepted Van Gogh in his own time. He sold one painting in his entire life. One. So if Rockwell had had any guts– and insight– he would have paired that painting with one of a rumpled Frenchman scratching his head while standing in front of “Starry Night”. That would have been a far richer, more subtle comment on modern art and the average American consumer.

But that would have made the opposite point that Rockwell intended. It would have shown that the public can be absolutely, totally, completely wrong about what is “good” art. It would have shown that the vast majority of people can be utterly foolish. It would have proven that it was quite possible for a mere illustrator to be the most popular artist in America.

This all begs the question. Is modern, abstract art, and its various derivatives, any good? The public has thrown up their hands. They don’t know and they don’t care.